By ANEEKA SIMONIS

“There is no glory in war. War, like old age, is not to be desired, but human nature being what it is there will be more wars … war is certainly the most disturbing factor in family and general life. The individuals who cause wars do not fight them. The memory of the general public is short-lived. – Frank Moore Dale (1892-1973) of Glencaple, Caldermeade.

TO MANY, Frank Moore Dale of Caldermeade was an outspoken jokester and highly successful dairy farmer.

But to his granddaughter Joyce Mills, he will always be remembered as ‘Pap’.

The 76-year-old Kooweerup woman, affectionately known to Pap as Tot, recalled memories of the ex-serviceman who left a flourishing, multi-million dollar farm to care for her and her mother.

Pap stood in to raise her after her father died in WWII.

“He and a few other men started Pura Dairy. He was there for many, many years as director of that dairy. When dad went to the war, Pap came back onto the farm which my dad ran and took over there. I was two or three,” Joyce recalled.

Frank Moore Dale was born in Wangoom outside of Warrnambool in 1892 where he enlisted to fight in World War I in February 1915 at 22 years of age.

He was trained at a military camp in Broadmeadows as an acting lance-corporal from 3 March until 23 April in 1915 when he was given four days’ final leave before departing for war.

Little did he and his family know, his emotional send-off marked the same day his younger brother, who was serving in Gallipoli, would lose his life.

“On 25 April while on that final day of leave, the first Australian Division landed at Gallipoli and on that day my brother, Edwin, was killed there while serving with the 8th Battalion,” Frank wrote in his memoir which he began writing in his seventies.

Edwin John Dale died at 19 years of age which was only known to his family, who for months clung to his status as ‘missing’, when his bagpipes were forwarded to them from the war office.

“Incredibly, amidst the terrible chaos of war, these battered bloodied bagpipes had been retrieved on the battlefield and returned to the family,” read the memoir.

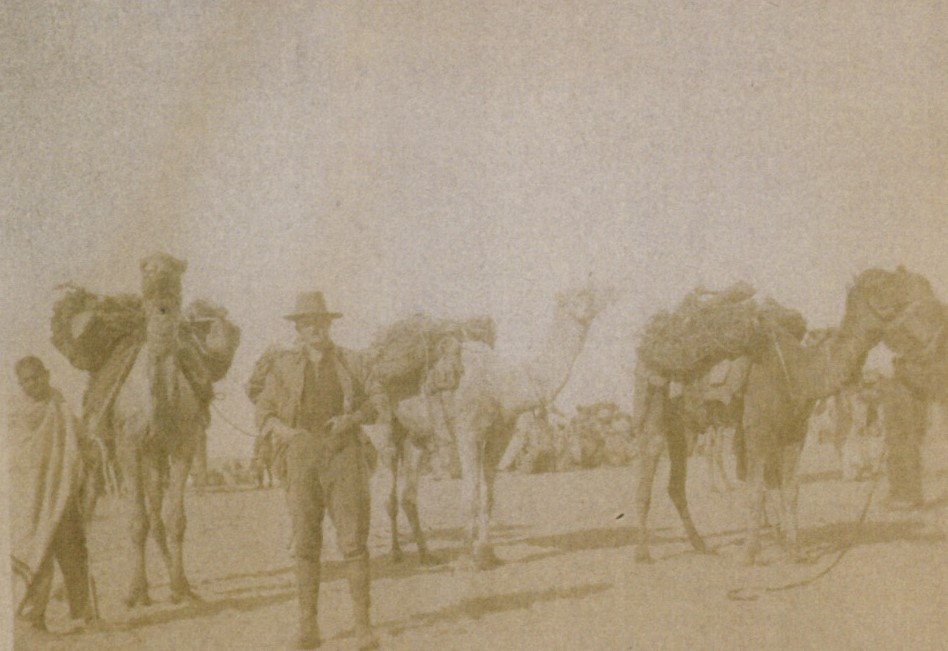

Frank left from Port Melbourne on 8 May 1915 en route to Egypt where he completed further military training before taking part as a corporal in the Battle of Lone Pine – known as one of most famous assaults of the Gallipoli campaign.

“Hundreds of dead Light Horse men were lying in no man’s land and it was not pleasant to gaze upon and impressed us deeply,” he wrote.

Frank copped a shrapnel bullet in his foot during the Gallipoli war effort.

He considered himself “fortunate in retaining good health” during the campaign where he stepped up to become a lance sergeant – though thoughts of his brother did not leave him.

“On several times I searched for my brother’s grave but was unsuccessful,” he wrote.

Frank was sent to France where he dug trenches during the Battle of the Somme under what he described as “heavy gunfire”.

“The artillery fire was terrific and there was much fighting in the area,” he wrote.

“We gathered our men and placed them on our objective and started to dig in so as to join up with the 7th Brigade on our right. All went well for a while although we were under heavy fire, then one of our own 19-pounders started dropping shells amongst us and the four men on my right were killed with one burst and I received a lot of the blast.”

Like many Diggers who spent months in the wet muddy trenches, Frank developed “trench foot” – a pain he described as “terrific” which had him removed from the war effort for seven months after being transferred to a hospital in Brighton in England.

“Many lost one or both feet. Evidently, there was not much that could be done except in bad cases where gangrene had set in, and that necessitated amputation. My feet were spotted black and quite stiff,” he said.

With both feet, Frank was discharged from hospital in January 1917 where he met his Scottish wife Jessie at a pub in England while studying to become a physical and bayonet training instructor as part of the war effort.

Once the armistice agreement was signed, Frank was sent back to France where he spent four months clearing the battlegrounds before returning to Australia in December 1919.

“For my parents, my homecoming must have left them with mixed feelings. Two sons had gone to war. One came home,” he wrote.

“There is no glory in war. War, like old age, is not to be desired, but human nature being what it is there will be more wars … war is certainly the most disturbing factor in family and general life. The individuals who cause wars do not fight them. The memory of the general public is short-lived.”

Frank and Jessie set up a ‘Glencaple’ dairy farm in Caldermeade in partnership with fellow returned serviceman Jack Wiltshire who was awarded the Military Cross and Bar after the war.

The two men served in the same unit throughout the entire war.

Frank went on to serve on the board of Pura Dairy, later known as Metropolitan Dairies Holdings Ltd) where Frank was still a director of the company when he began writing his memoir.

Frank and Jessie unsuccessful tried for a family before Joyce’s mother Jean came to live with them on the farm from Scotland.

Jean went on to marry George James Coleman in Lang Lang on 23 December 1935 and later gave birth to Joyce.

“The young couple took over management of my farm because at this time, I was assisting in the establishment of the Pura Dairy in Melbourne. They continued in this capacity until 1940 when George enlisted in the 2nd AIF. I returned to ‘Grencaple’ and with Jean’s assistance worked the farm,” he wrote.

Joyce was 18 months old when her father enlisted.

George served in Rabaul in New Britian as part of the 2nd/22nd Battalion and was killed on 21 January 1942.

“I did what I could to fill the gap caused by George’s death. I hope that in this respect, my efforts were successful,” Frank wrote in his memoir.

Joyce said Pap, or Frank, was an incredible role model who remained a large part of her life until he died in 1973.

“I could go to him with all my problems. In fact, I went to him before I went to Mum. Even after I was married and had kids, it was Pap I rang up for problems,” she recalled.

“Pap made sure I had a pony from a very young age because my father was a great man for horses and he thought one of my dad’s wishes would be that I had a pony.”

Frank Moore Dale died on 22 July, 1973. Joyce was there with him. Frank’s wife Jessie died three months later.