By GEORGIA WESTGARTH

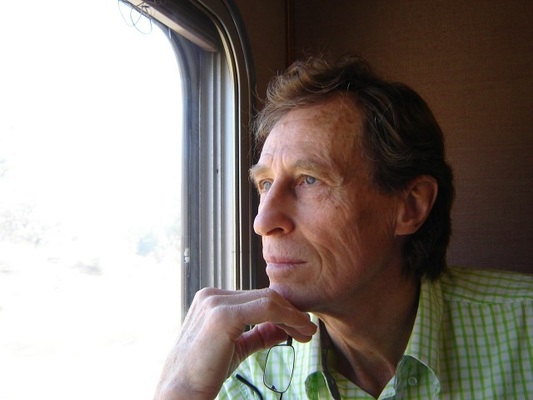

JOHN STEWARD has lived in some of the most remote corners of the world and now resides in Junction Village. John sat down with GEORGIA WESTGARTH to discuss his life as a World Vision consultant and the book he wrote in the warmth of the Tooradin Anglican Church.

MANY compared it to trying to drink from a waterfall – but for John Steward it was a journey of personal development for himself and a nation’s people.

Trained in agricultural science at Adelaide University, John was no expert in teaching or healing hatred but it was through his own personal development that he found a way to help a country overcome its biggest barrier – genocide.

In the Rwandan genocide of 1994, it was John’s job to help heal the mourning, the bitter, the distraught and the lost people of Rwanda.

Some 800,000 men, women and children perished in the slaughter.

“When people would hear what we were trying to do, they would say, “That’s like trying to drink from a waterfall” – gushing out everywhere at high speed – it was a great description,” John said.

“When I got to Rwanda I thought, far out, everyone was a victim, they were either a perpetrator, related to a killer, related to someone who was killed or participated in looting – you could feel the hate in the room.”

But before John made it to Rwanda with World Vision and long before he knew his mission in life he started his love affair with Indonesia – describing the three years from age 9 to 11 as the best years of his life.

“My dad ran a hospital for the Indonesian Government and after correspondence classes with my mother I would take my shirt off and run through the rice fields, catch fish and climb coconut trees.

“I returned as an adult with my wife Sandy and two daughters to do communication development workshops with the Javanese people – we were there for nine years,” said John.

After making a name for himself and teaching the Javanese to be independent, John was approached by World Vision.

“They asked me to visit their agriculture programs and tell them what I thought,” he said.

“I told them that their workers were amazing but that there was a problem with their attitude in that they are trying to bring ideas from outside and not letting the ideas come up from underneath.”

John had learnt the best way to teach was to listen and train in a way so that the teacher didn’t become “paternalistic”.

“It’s not about telling the community what they should do and when World Vision asked me to set up my own training program in Java I said on one condition – that a Javanese person is appointed to run it, not me,” he said.

John left the program he started after four years and it was run by the Javanese for more than 25 years.

“I was tired of hearing expatriate missionaries and aid workers say they’d been training for 15, 20, some 32 years and when asked when they were planning on leaving they would say after we’ve trained the locals,” John said.

“They had taught them things in that time but they hadn’t mentored or empowered them and that’s the difference.”

John got to watch people weave cloth and grow crops for the first time and see how it could change their lives and the community as a whole.

Six hundred people were trained as community leaders through that program and John was asked to travel around the word to teach World Vision workers his self-taught, practical program.

“I don’t have a degree in tropical agriculture, I just learnt on the job,” he said.

For more than 13 years John flew from country to country and at 50 years old he was given his most daunting task of all – peace and reconciliation for World Vision to mend the broken, post genocide, Rwanda – a landlocked country in East Africa.

“World Vision got involved in Rwanda in 1996 doing community development work and quickly realised that people were still angry, had enemies and wanted revenge.

“They realised the work they were doing could all go up in smoke and things would be chaos if they didn’t fully recover from the anger and pain of the genocide,” John said.

With his daughters, Simone and Adele now married, John and Sandy started a new chapter in Rwanda where John applauded the healing program written by Professor Simon Gasibirege, already in place in Rwanda.

“I told World Vision they had to continue with Professor Simon’s program which he gave a very innocent name, ‘personal development workshop’ because I knew it worked,” John said.

“I guaranteed them every Rwandan that does the workshop will double their productivity in their World Vision work.”

John was so impressed by the workshop because he had learnt virtually the same techniques at a men’s group he joined in Doveton two years before.

“I joined the group to learn how to be different,” John said.

It was his dad’s WWII ‘boys don’t cry’ influence that had led John to clam up his feelings and it was the Doveton men’s group that taught him valuable lessons for his work in Rwanda.

“At 48 years old I went to that men’s group for 16 months and that began my process of change and I had no idea at that time I’d end up in Rwanda,” he said.

With the help of his experience in Indonesia, the Doveton Men’s Group and John’s own journey to self-empowerment he helped mend the horror of the Rwandan genocide and watched many miracles of forgiveness unfold.

“We put more than 250 World Vision staff through Professor Simon’s workshop so they could be healed themselves because the genocide had traumatised everyone.

“Thousands of people were helped by passing on what they had learnt,” he said. John then became a World Vision consultant for a Rwandan youth project and returned to Rwanda 18 times over nine years.

John has written four books in his time, his most recent book, ‘From Genocide to Generosity’, was launched this year and tells his story and the many stories of the Rwandan healing process.

His book is dedicated to all the people who are still healing.