By DANNY BUTTLER

FOR every hero lauded during the Anzac Day centenary, there will be another thousand Thomas and Patrick Faheys.

There are no chapters in military history books devoted to the exploits of these unfortunate former students of St Patrick’s, Pakenham. No larrikin movie characters based on the doomed brothers. No myths. No legends.

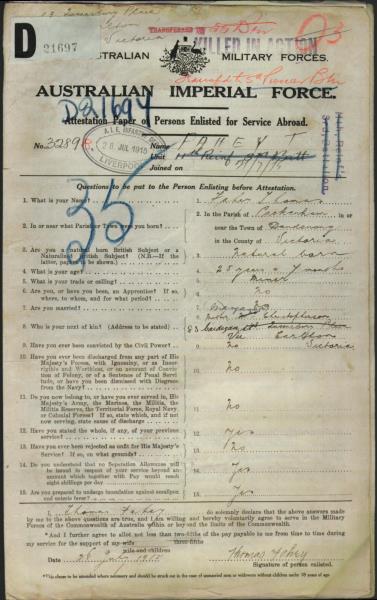

Their warrior legacy is a pair of headstones in Pakenham cemetery, broken bodies forever lying in foreign soils and a meagre paper trail that ends with three heart-wrenching words sent to their widowed mother.

“Killed in action“ for 27-year old Thomas. “Died of wounds“ for his little brother.

For Thomas, death in the firestorm of the Western Front was catalogued by a cold bureaucracy remarkable only for its brevity and lack of detail.

He may have fallen charging an enemy machine-gun to protect his mates or died weeping in a freezing trench as German shells rained down from the leaden skies above France.

Maybe no-one saw him die. Maybe those who witnessed his last moments were also swallowed up by Europe’s tide of death.

Killed in Action was all there was.

We know how he left Australia and where his remains lie. The rest of his brief soldier’s life is contained in a few poorly-typed lines on official army forms.

From his 2 November, 1915 departure from Sydney on HMAT Euripides – appropriately named after the writer of Greek tragedies – Thomas’s life is captured neatly in a two-page summary.

It tells us that, after a bout of mumps in Abbassia just before Christmas 1915, he was transferred between battalions, ending up with the 5th Pioneers based at the Egyptian training camp of Tel-El-Kebir.

There’s no record of active service, just a forfeit of two days’ pay for being absent without leave for 24 hours in February 1916.

In June that year, Thomas boarded the “Canada“, crossing the Mediterranean from Alexandria to Marseille. It was his last sea voyage.

From there, he almost certainly would have taken a troop train north, ending his journey in the infamous trenches of the Somme near the Belgian border.

More than one million people were killed or wounded during the Battle of the Somme. It was one of the bloodiest battles in the bloody history of mankind and achieved next to nothing.

A German officer wrote of the Somme that “the whole history of the world cannot contain a more ghastly word.“

It was in this nightmare of mud and blood that Private Fahey spent the last months of his short life – dying “in the field“ on 18 November, 1916 – the Battle of the Somme’s final day.

Over the following months and years, a trickle of information arrived for his widowed mother at her home in the slums of Carlton.

A telegram announcing Thomas’s death was followed by his meagre possessions, two pounds in pay that he was owed and a letter confirming the location of his grave in the Quarry War Cemetery near Montauban, France.

Much later, medals were issued. Records show the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal were sent home in coming years.

Less than a year after Thomas died, Private Patrick Fahey was the family’s second sacrifice to the insatiable Western Front.

In the previous two years, official records catalogue a run of wounds and illness that had seen him hospitalised, but sent back to the front each time.

Arriving at Marseille in June 1916, he joined the 5th Pioneers – the same battalion as Thomas died with.

Within two months of arriving in northern France, Patrick was shot in the buttocks and shoulder and transferred to England to recuperate from the serious wounds.

Four months later he was discharged from hospital and marched back to the front, possibly joining Thomas for his older brother’s last weeks on earth.

A year later he was admitted back to a field hospital with scabies, a highly contagious infection caused by mites that were rampant in the trenches during the warmer months.

Rejoining his unit, Patrick crossed the border into Belgium where his luck finally ran out.

Shrapnel penetrated his thigh and abdomen on 15 October, 1917. A day later, he died of the wounds at the Canadian Clearing Station in Belgium. Private Patrick Fahey was 26 years old.

Like his brother, there’s no official record of how he died. Just a hand-written sheet, later typed out neatly, that he “died of wounds, in the field, Belgium.“

Mary Fahey received Patrick’s worldly goods a year later. A wallet, notebook, diary, religious book, cards, letters, metal ring, disc, photos and scapulars were all that remained of Mrs Fahey’s second lost boy.

With the war still grinding on, Pakenham’s St Patrick’s Catholic School was already honouring its old boys who served in the war, including two more Fahey brothers, Edward and James, who appear to have survived the trenches.

On 26 April, 1918, the Pakenham Gazette reported on a ceremony at the school in which a “huge“ honour board of “blackwood and Queensland oak“ was unveiled.

Among the dead were A. Clancy, T. Dywer, T. Halloran and Thomas and Patrick Fahey, all of whom “made the supreme sacrifice“ during the previous three years.

Speaking to the gathering, Father Mernor, who was reportedly new to the district, captured the young nation’s patriotic fervour that saw so many boys like Thomas and Patrick churned into bloody “heroes“ of the Empire.

“This was true patriotism. That Australians were patriotic was shown by so many laying down their lives. All were proud of their achievements,“ he said.

“We all regretted the loss of our brave men, but their loss was proving our gain as it but needed this baptism of blood to cement all creeds and classes.“

Lest we forget.