By KATHRYN BERMINGHAM

“I have great memories on this land.”

AT the back of Peter and Mary-Anne Hams’ Tynong property lies a hidden piece of Australian history. The quarry on the Hams’ land provided the silver-grey granite used in the construction of Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance, the central war memorial in Victoria. However a sunset walk over the hill and down to the deserted quarry would reveal no sign that this was the source of such a prominent Australian landmark, as KATHRYN BERMINGHAM discovered.

LOCALS may know the Hams’ Tynong quarry as Granite Hill.

World War I rocked Australia, and established the nation in many ways. With a total of more than 60,000 killed and 155,000 injured, the fledgling nation searched for a way to remember the fallen. The concept of a shrine was suggested by the newly-formed War Memorials Advisory Committee, of which Sir John Monash was a key member after his involvement as commander of the Australian forces in the war.

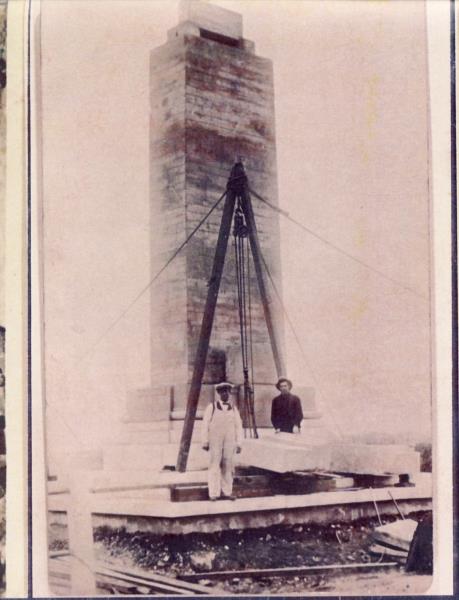

A competition was held in 1923, inviting the people of Victoria to submit designs for a Great War Memorial. The winning design, the shrine that stands today, was submitted by architects and returned servicemen Philip B. Hudson and James H. Wardrop. The plan received widespread criticism for its linear exterior design and perceived lack of elegance. This was a structure that was designed to remember Australia’s war heroes for centuries to come.

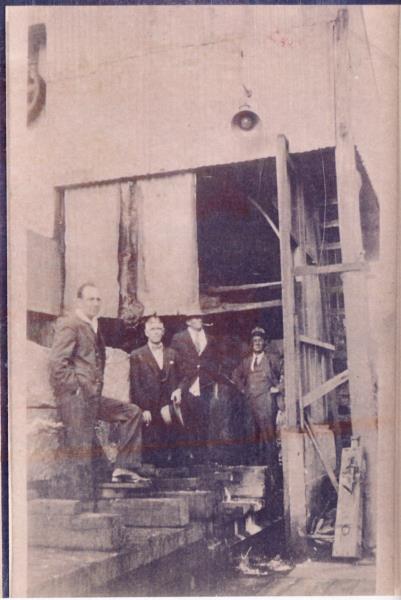

With the future in mind, tenders opened to stonework businesses vying for the contract to erect the shrine. The contract was one by Vaughan and Lodge, four brothers from the town of Hamilton in Western Victoria. The foundation stone of the shrine was laid in 1927 by the Governor of Victoria, Lord Somers, before work officially began in 1928.

A plaque outside the Tynong Public Hall reads: “Local amateur geologist, Mrs Mary Ann Ryan, suggested to the National War Memorial Committee that granite from the original Tynong quarry be used in the construction of the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne.”

After taking samples of the rock into Melbourne for inspection, the rock was selected and mining began in 1928.

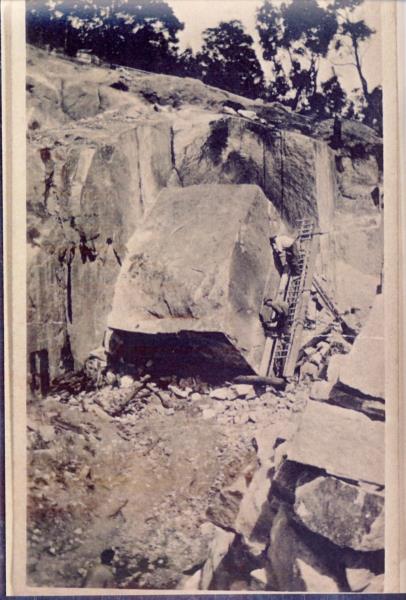

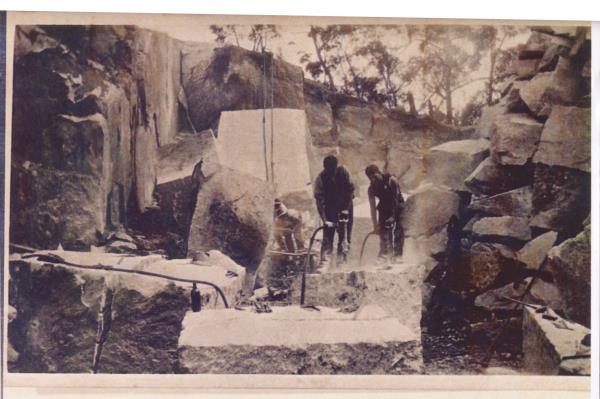

Vaughan and Lodge believed in providing jobs for returned soldiers, and hundreds of them lined up for work at Granite Hill. Machinery was imported from America specifically for the project, including a saw used to cut the granite into smooth blocks. Water was regularly used to cool the saw, and it was hard work. The rigid structure of Tynong granite made it ideal for use at the shrine but difficult to extract with the equipment of the day. Holes six to eight inches deep would be hand-drilled into the rock and loaded with explosive, before workers vacated the area and the explosive detonated. The granite was collected and sent to Melbourne to be fashioned into the shape it takes today.

The process continued for six years, and so many men worked at the quarry that a boarding house was established in the tiny town. The quarry put Tynong on the map, and electricity from the state power line was connected to the quarry in 1929, benefitting the entire community.

While initially controversial, the people of Melbourne grew to appreciate the new structure and it was officially opened by the Duke of Gloucester on November 11 1934, at a ceremony attended by about 300,000 people.

Opened solely for the purpose of the Shrine, the quarry closed for a period following its completion.

All Australians have a connection to this land. For the Hams family, it’s deeply personal. In the early ’50s, the Hams family moved onto the property and re-started mining from the quarry.

“My grandfather brought the property in the 1950s. He went to New Guinea in the Second World War, and he lived here with his family when he got back,” Peter recalls.

“They brought it at the wrong time. The work was hard and they stuck at it but they didn’t make any money.”

With his three sons, Peter’s grandfather Frederick formed mining business ‘F.G. Hams and Sons’ and acquired other quarries in the area.

Though the work was hard and largely unprofitable, the business contributed to a number of roads and monuments still standing today, including the initial bridge linking San Remo to Phillip Island and a number of war memorials. The rock outside the Tynong Public Hall reminds locals of the important part that the quarry played in the formation of the town.

Around Victoria, preparations for the centenary of Anzac Day have been underway for several years. The State Government’s $45 million redevelopment of the shrine has included the addition of new galleries and displays, the role of the memorial shifting towards an educational one as numbers of veterans decline.

Naturally, those involved in the redevelopment wanted to source the granite from the Hams’ Tynong property. Similar to the issues faced by the Hams family in their early days on the property, the rock remains too difficult to mine.

“The idea was probably a bit romantic, it wouldn’t have been logistically possible,” Peter said.

“The water levels are too high, the rock is hard. It’s just not practical to mine there anymore.”

The granite for the redevelopment was sourced from a similar quarry in the area, ensuring the silver-grey stone of the shrine is retained.

The quarry is now listed as a site of significance with both the state of Victoria and the Cardinia Shire Council.

Peter and Mary-Anne Hams insist this story isn’t about them – they are merely keepers of this important part of Australian history. They now live on the land with three of their children: Nick, Hugh and Eugene. Their daughter, Pia, lives in Melbourne.

While their quarry has been widely celebrated as an important piece of history and crucial in the commemoration of Australian war heroes, the Hams also hold a simple appreciation for this place.

“It’s a beautiful area, we love it here,” Peter says.

“I have great memories on this land.”