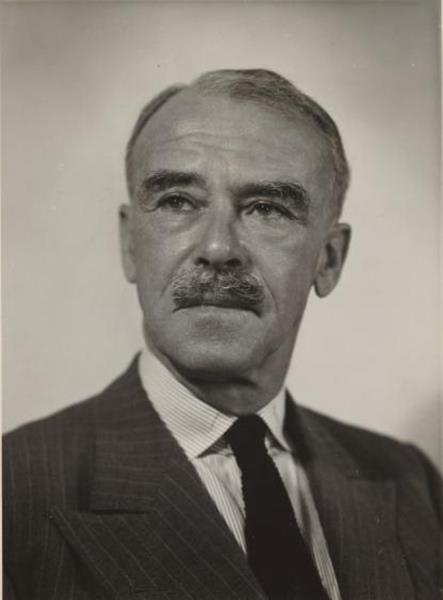

Two prominent owners of Berwick’s iconic Edrington Estate played a major part in the war effort – from different perspectives. Prominent businessman and sporting identity Andrew Chirnside, who had the property during those years, was a regular and generous contributor to the various patriotic funds and would later donate a fair slice of the estate to the government’s Soldier Settlement scheme. Years later the property passed to World War I veteran Lord Richard Casey, who lived at the property as Australia’s 16th Governor General. A statue will be unveiled in Berwick today in his honour. ANDREW CANTWELL reports on two of Berwick’s most famous citizens.

THE City of Casey borrows its name from Lord Casey, a resident of Berwick and one-time Governor General of Australia – and a veteran of the Gallipoli campaign.

He would later serve on the Western Front and rise to the rank of Brigade Major. He never commanded troops, instead working in planning and intelligence, but he was twice decorated for bravery in forward observations and visits to the front lines, winning a Military Cross and DSO.

He had a reputation for being industrious, pragmatic and even-handed, and became known early for his keen observations and assessments.

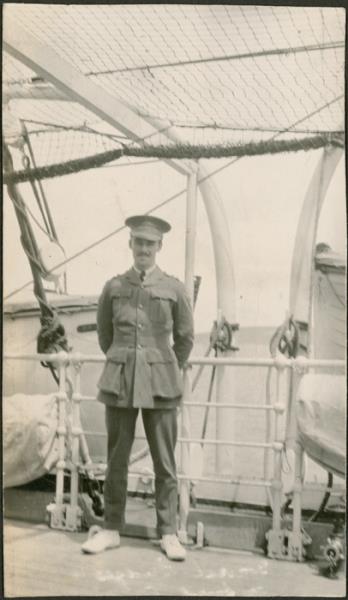

As a graduate mining engineer with one year of service in the King Edward’s Horse Regiment, and from a family of means, Dick Casey qualified for officer status.

A letter from his well-heeled father promised a car for the war effort – provided at no public expense – if the son were approved for service. His service records show he was appointed to the Automobile Corps.

Lieutenant Casey had the good fortune to be appointed an Orderly Officer and Aide-de-camp to the Australian Major-General Sir William Bridges in Egypt before Gen Bridges was dispatched to Gallipoli as commander of the Australian 1st Division. Bridges is chiefly remembered for being killed at Gallipoli within three weeks of the landing.

Lt Casey landed at Gallipoli with the first waves on 25 April 1915, and was in and about the trenches until October, when severe dysentery forced him from the peninsula. He’d been battling the condition for two weeks.

His war diaries and many photographs from the conflict are among an extensive collection gifted by Lord Casey to the Australian National Archives in Canberra.

His Gallipoli diary gives insight into conditions in the trenches and the attitudes of the men who looked death in the face every day. He shared an early enthusiasm for the great enterprise, which – in light of the increasing carnage and deteriorating conditions – gave way to a depression and then a professional military detachment.

Early diary entries are long and descriptive, providing insights into the movements and thinking of senior commanders. They chronicle the high spirits and bravado of the men, contain sketches of the trenches and emplacements – and the innovative ways the Diggers dealt with the extreme conditions they were in.

The landing itself is covered in an extended entry:

“At about 3am the 500 men who we had on (the transport ship) the Prince of Wales started to get into the boats and form up alongside the Prince of Wales as tows. Same on the (ships) Queens and the London – primary landing party thus being 1500 strong and the remainder of the brigade – 2500 – being landed from the transports onto five torpedo boat destroyers.

From the destroyers they transferred into boats and rowed on. It so happens that we landed about a mile north of where we had intended – i.e. a little north of Gabba Tepe. We on the Prince of Wales landed at 5am from a trawler transferring to a rowboat about a couple of hundred yards from the shore.

As we got to about 30 yards from beach we were greeted by shrapnel between us and the beach from the confounded Gaba Tepe Battery. If they had landed a second one in the same place as they usually do the Division would have been minus its staff very early in the proceedings. However, we got ashore safely about two miles above Gaba Tepe and had a good initial and salutary dose of shrapnel for about an hour. Then it started coming from inland and carried on from these two sources all day. And we had a lovely day for it. The 3rd Brigade under Colonel Maclagan had made good their landing – first taking the shore trenches at the point of the bayonet. The Turks fled and our men went perhaps too far as they had no immediate supports … we made dugouts in the morning. They had to be cunningly done to protect us from two directions – more or less open affairs with the most primitive of material.”

And later in the day:

“Went with the G. (general) and Col. White and had my first taste of fire.”

Shortly after he would write that the botched landing had worked out to be a godsend, saving the landing troops from what the Turks had prepared for them – from 30 April:

“First made observations from the gun position on right (Bob Down Pitt). This overlooks Gaba Tepe and one can clearly see the wire entanglements laid just above the water’s edge, all along the bay – also the Turks’ carefully made trenches – first and second line and communications – just over the ridge. It was Providence that let us land north of this bay and not in it as was intended.”

Although bogged down by terrain and the fierce shelling, the young lieutenant was initially dismissive of the skill of the foe. Just days after the landing, on 28 April, he wrote:

“They sling a 12” shell at the ships now and again – makes a prodigious splash, but nothing more.”

He later writes of the Diggers having a laugh at being able to fire off five or so rounds to incite up to 30 minutes of fire from the Turks, wildly aimed and the bullets falling harmlessly.

Though he acknowledged that the relentless shelling and lack of room to manoeuvre were taxing – from 31 April:

“Being under rifle and shell fire is quite alright talking about it afterwards, but it is extraordinarily unpleasant at the time … It’s a curious war when Division and Army Corps Headquarters are under shell and rifle fire every day, and one can stroll out from Headquarters (and the base!) and be in the fire trenches in a few minutes.”

Although bogged down, the troops were keen to make the most of the position. Lt Casey recorded an exchange on 29 April:

“The Turks make feeble attempts to charge at times shouting ‘Allah – Allah!’ Our fellows wait until they get to within 40 yards then out on them – ‘Let the ***** come – we’ll give ’em Allah!’ ”

And on the good spirits of the men, from 14 May:

“Some of our fellows’ remarks today were rather funny. Some were at their food when we came along – three generals – ‘Look out Bill, – keep your eye on them biscuits – ‘ere comes three bloomin’ generals!’ Also a remark to our escort ‘Ullo – where’d yer get the prisoners!’ ”

He also learned early that although he was a member of the general staff, his safety was by no means assured – not just from the enemy fire but also from the practice of his commanding officer of regularly visiting the front lines. From 28 April:

“Everyone tries to persuade the G. not to go up into the frontline but it is of no avail. He seems to love to be where the firing is hottest.”

It was such a visit to the front lines that cost Gen Bridges his life. The General was shot through the right leg on 15 May, the bullet severing his femoral artery. Dragged to safety and his wound plugged at a nearby dressing station, he was evacuated to the hospital ship the Gascon, and after exploratory surgery his leg marked for amputation. But the wound developed an infection and the General succumbed on 18 May.

Lt Casey was with General Bridges when he was shot, and had just run the same stretch of open ground.

The death count and the lack of movement began to take their toll. After some weeks of being tied down with little prospect of advancing from the trenches, Lt Casey wrote on 16 May:

“This game gets rather sickening. I get fits of rather severe depression at times. It all seems so hopeless and endless and sordid. Tied down to a few square miles of steep hilly country – plastered with shells from well concealed positions – no freedom of manouevre and no getting on.”

Later diary entries are perfunctory, merely noting the weather and whether there had been action.

This entry – written at the end of the Allies’ month-long August Offensive – is briefer than most:

“Sunday 29.8.15. My birthday.”

His diaries from later in the war provide little of the detail – and none of the dark humour – of daily life he captured at Gallipoli.

Lord Casey, like many of his era, is said to have seldom spoken publicly of his war service – but the lessons he learned and the relationships he established were to serve him well over the rest of his life.

He held Australia’s first diplomatic posting to the US at the outbreak of WWII; when Labor came to power under John Curtin in 1941 he left for England where Churchill appointed him to several positions including the British War Cabinet, the British Resident Minister of State for the Middle East towards the close of WWII and then as the last British Governor of Bengal between 1944 and 1946, where he met with Gandhi many times.

He had earlier served as the Joe Hockey of the time, as Federal Treasurer between 1935 and 1939, and after WWII – amid the rise of the Iron Curtain and the growing tensions of the Cold War – held the External Affairs (Foreign Ministry) portfolio between 1951 and 1960. The building housing the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in Canberra is named in his honour. From his time as the minister responsible for the CSIRO, Casey Station in Antarctica is also named after him.

He retired from politics in 1960 and was granted a rare life peerage as Baron Casey by Queen Elizabeth II, he took a seat in the British House of Lords but was recalled to public service in Australia when Menzies recommended him at the age of 75 for the position of Governor-General. He was the third Australian to hold the high office, and the first nominated by a conservative government.

He retired to the family property “Edrington” at Berwick in 1969.

A car accident in 1974 contributed to his death in 1976.

Lord Casey also lends his name to the Federal Seat of Casey, in Melbourne’s east, held by Liberal Tony Smith, and covering the northern Dandenong Ranges and Yarra Valley.

He was also the first to hold the adjoining Federal seat of La Trobe when that seat was first declared in 1949, and now held by Liberal Jason Wood.