By Garry Howe

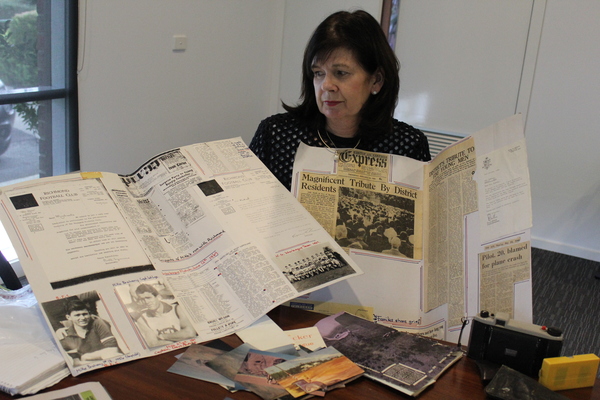

THE loss of five Bunyip mates in a Northern Territory air crash rocked the district almost half a century ago and still tugs at heartstrings today.

Memories of that disaster came flooding back for Berwick woman Jo Scanlon last month when two of her sons, Ben and Seamus Scanlon, joined a few mates to retrace the steps of that tragic journey.

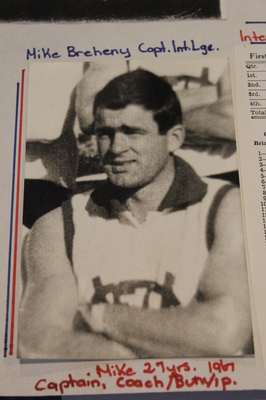

Champion local footballer Mike Breheny – her brother and the boys’ uncle – was one of the five killed when the Cessna they were flying in came down during a tropical thunderstorm just short of Daly Waters airstrip on 29 December 1967.

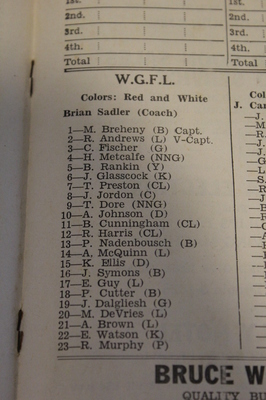

The 27-year-old was coach of the Bunyip Football Club and captain of the West Gippsland interleague side that year. As a tribute, the league best and fairest medal was presented in his honour for the best part of four decades and the Bunyip award still carries his name.

Others on the flight were 27-year-old farmer Peter Kay, 23-year-old Kooweerup primary school teacher Barry Sullivan, 34-year-old Bunyip milk bar proprietor and phone technician Noel Heatley and 25-year-old Bunyip printer and newspaper proprietor Don Smith.

A monument erected in their memory still stands at the entrance to the Bunyip Recreation Reserve.

The pilot, 20-year-old Peter Limon of Croydon, was also killed.

It later emerged that Mike had survived the impact and had died from the effects of multiple minor fractures and exposure at some stage during the four days it took rescuers to locate the wreckage in the remote bushland.

“My mother always felt in her heart that he hadn’t died straight away,” said Jo, who was 15 at the time of the accident.

“It was just so tragic and terribly sensitive at the time. A lot of people took it very hard and many didn’t want to talk about it.”

The death certificate, when it arrived some time later, confirmed her mother’s fears.

Abe Kay, the father of Peter, had joined the search party and was one of the first on the scene of the crash. He told the Brehenys that Mike was the only one he could recognise and at first appeared to be still alive, leaning back as if asleep.

They surmise that Mike was sitting on a stool at the back of the aircraft and had been thrown clear as it approached the ground.

Jo said the boys had sought to hire a six-seater plane, but had ended up with a four-seater, which meant someone had to sit up the back on a stool.

Hauntingly, a postcard arrived from Mike while the plane was still missing and it confirmed they had twice shed luggage to lighten the load – the first time at Moorabbin before leaving and then again at Darwin because of the “light air”.

Mike was writing the card on the eve of their tragic leg while sitting on his bed in a Darwin hotel unable to sleep because of the high humidity, with Barry Sullivan writing another card beside him.

They touched on how remote the outback was, explaining that news like the recent disappearance of Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt took three days to find its way to Ayers Rock.

“By the way,” it ends. “Talk about Ayers Rock being remote. They did not know about the PM’s disappearance until three days later, also the result of the Melbourne Cup is three days later. Well, I better close now. Hoping this card finds everybody in the pink.”

There was a PS that said: “Yes, you might get another one”.

She wouldn’t. The next day’s flight went horribly wrong.

The touring party set off from Darwin at 3pm, aiming to be at McArthur River Station just after 6pm to stay there the night before going on to the Queensland leg.

However, just after 5.30pm, they had changed course to avoid an approaching thunderstorm.

For the next three hours, the pilot changed route a number of times to avoid the worst of the weather and made several unsuccessful attempts to land, before air traffic control diverted them to Daly Waters airstrip.

Low on fuel and now flying without lights in the darkness, the only glimpse they got of the ground was through lightning flashes.

The last contact from the plane came at 8.40pm and the wreckage was not found for four days, 28 miles north east of its destination and only eight miles east of the Stuart Highway, the only strip of road on the barren landscape. They were only 14 minutes from safety.

The aircraft lost one wing when hitting a tree, then gradually disintegrated as it crashed at high speed in the heavily timbered area.

Mike’s camera was recovered at the crash site and the photos, when developed, showed the group on the first leg of the journey at the likes of Ayers Rock and Tennant Creek.

Jo still has the camera, along with the slide case, Mike’s wallet and the rosary beads his mother gave him to ensure he was safe. They broke apart on impact and are now safely stored in a leather pouch.

Ben, Seamus and the boys on the more recent trip had a look at the photos upon their return and remarked how similar the landscape was to 1967.

“The airport at Tennant Creek looks exactly the same today,” Seamus said.

Seamus, Ben and their travelling mates were taken by how barren the landscape was and felt for the ’67 travellers in those final hours.

“It really brought it home to us,” Seamus said.

“You see how remote it is and it probably hasn’t changed a lot.

“I have done a fair bit of travel and seen a bit of the world, but you don’t realise how big the Territory is. You just don’t see anything for days.

“What we came to realise – and unfortunately they would have known as well – that if you come down in the middle of nowhere, you’re in a bit of trouble. It’s not a matter of walking to the closest road. This is some of the harshest country you can fly over.”

The Scanlon boys say they grew up hearing stories of the crash from the likes of Ron Banbury, Phonse Cunningham and Tom Cleary.

“As kids we probably didn’t comprehend how big it was for the district,” Seamus said.

“As we get older we respect the story a bit more and realise the gravity of the situation and how the community would have felt it back then.”

Jo was a bit of a mess the whole time the boys were away. She was confident they would make it home, but says it was “very emotional”.

Her cousin Bill Guinane heard about the boys’ trip and came over to visit to make sure she was okay.

His brother Paddy, a former Richmond footballer, was supposed to be on the trip as well, but was one of a few to pull out at the last minute.

Ron Banbury was another – and local identity Gerry O’Donnell. The trip was planned in Gerry’s loungeroom, but he had to back out because he didn’t have the money.

The crash has been a constant in Jo’s life.

A few years back, around the 40th anniversary, the brother of 20-year-old pilot Peter Limon made contact. They met once and agreed to stay in touch, but that hasn’t really happened.

The crash was put down to pilot error and attempts to delve deeper into the causes were thwarted when fire ripped through Moorabbin airport.

“Their family suffered too,” Jo said. “They ended up moving out of the area and I don’t believe his mother could ever talk about the crash.

“It had a real domino effect and chain reaction, impacting on so many people.

“Nothing was ever the same again.

“I’m just happy the boys were interested enough to make the trip and grasped what happened all those years ago.”

Read more

[ Trip revives crash heartache ]

[ The twists and turns of final hours ]

[ ’Those magnificent men in their flying machine’ ]

[ Four states for mates ]