This edited extract from an eight page report on the Northern Territory air disaster in December 1967 provides a detailed account of the fatal flight’s final hours.

SHORTLY after 3pm on 29 December 1967, a Cessna 206 with the pilot and five passengers on board, took off from Darwin to McArthur Station, 390 nautical miles to the south-east.

The flight was the homeward leg of a two week aerial tour from Melbourne, which the six occupants of the aircraft had begun three days before.

The party flew from Melbourne to Darwin via Mildura, Leigh Creek, Oodnadatta, Ayers Rock, Alice Springs and Tennant Creek. The return flight from Darwin was to be made via McArthur River, then to the east coasts of Queensland and New South Wales before returning to Victoria.

It was a typical day for the northern Australian wet season – hot, humid and unsettled.

The pilot, who had made two previous flights to the Northern Territory, ordered a route forecast, which indicated northerly winds of 15 knots, scattered showers and isolated thunderstorms over the route, particularly towards the coast.

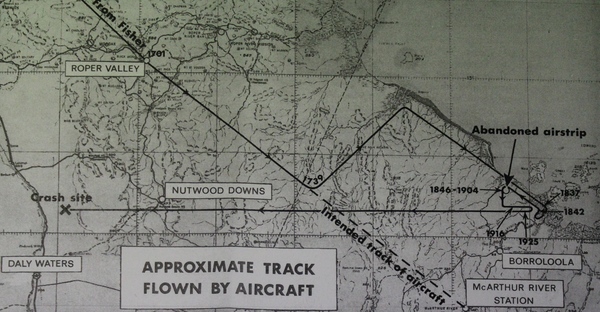

He studied the information and then submitted a detailed and accurately compiled flight plan covering the route to McArthur Station via Fisher and Roper Valley. The flight was scheduled to take 174 minutes, with enough fuel for a 305 minute journey.

The pilot set course at 3.08pm, with an estimated arrival time of 6.02pm, nearly 90 minutes before last light.

An hour later the aircraft reported over Fisher, 125 miles south east of Darwin at 2000 feet, only a minute behind schedule. At 5.01pm, it was still at 2000 feet and flying over the Roper Valley aerodrome, six minutes behind, indicating the aircraft had encountered little wind between Fisher and Roper Valley and was making good its true airspeed of a little over 120 knots.

At 5.39pm, the pilot called Darwin again to advise he was 70 miles west of McArthur River Station and was diverting to the north to intercept the coast because of heavy rain and turbulence associated with thunderstorms on the direct track. The plan was to now proceed to the destination “via the coast”.

At this point, communication with Darwin Flight Service Centre was becoming difficult.

At 5.46, the pilot advised that he was 45 minutes behind schedule and revised his arrival time to 6.31. Half an hour later, it was amended again to 7.04pm.

At 6.42, the pilot reported he was over the mouth of the McArthur River, but was “unable to proceed VFR (visual flight rules)” and was diverting to Roper River Mission, 120 miles to the north-west.

Three minutes later the pilot reported seeing an abandoned airstrip about 10 miles north-west of the river mouth and advised that he would land there, but called again at 7.04pm to say it was not possible because of “extremely high winds”.

The pilot had the impression the weather had cleared up a little to the south, so he headed for Borroloola, also on the McArthur River, but 25 miles nearer the coast than the station.

At 7.16pm, the pilot reported “I’m unable to land anywhere in this area due to bad weather and high winds” and asked whether night landing facilities were available to Normanton, 300 nautical miles east.

Darwin replied that Normanton was not achievable, given the aircraft’s remaining endurance was only 90 minutes, and suggested they divert instead to Daly Waters.

As the end of daylight was due at 7.24pm, Darwin introduced the Uncertainty Phase of search and rescue procedures.

At 7.30pm, the pilot advised that he had set course for Daly Waters and at 7.42pm the rating had been upgraded to Alert.

In response to further inquiries from Darwin, the pilot said his last known position was the mouth of the McArthur River at 7.25pm and he had since been maintaining a heading of 260 degrees magnetic – prompting an upgrade to Distress Phase.

The needle in the aircraft was wandering because of the distance and thunderstorm activity and the pilot was told the runway lighting and rotating beacon had been turned on at Daly Waters airport.

At 7.55pm, he advised his remaining fuel was “probably enough for about 60 minutes”.

Ten minutes later a special weather report was passed to the aircraft – wind from 150 degrees at 13 knots, gusting to 21 knots, visibility 800 yards, with two-eights of cloud at 1500 feet and six-eights of cumulo nimbus cloud at 5000 feet.

The pilot then reported he was flying in cloud and descending to 1000 feet. Ten minutes later he said he was at 1300 feet, in and out of cloud, and flying in rain.

At 8.25pm, he told Darwin the aircraft’s port tank had run dry and that, as he had not fuel indication on the starboard tank gauge, he was uncertain of how much fuel they had left.

Two minutes later, he said that from the moments of visibility during lightning flashes, he could see the aircraft was getting close to the ground and he thought it was inadvisable to descend any further. The auto detection finder (ADF) was not giving any positive indication.

Questioned at 8.30pm as to the amount of fuel left, the pilot replied “About 10 minutes, but I think not too much”. Then asked if he could see anything, the pilot replied that from occasional glimpses of the ground during lightning flashes, there appeared to be low stunted trees beneath him.

Darwin then gave the pilot a frequency to listen to if he was forced to land.

At 8.36pm, the pilot said the ADF was now giving some indication that the plane was heading towards Daly Waters and confirmed that he was still maintaining a heading of 260 degrees, flying in cloud and rain.

Asked at 8.40pm if he could see the ground, the pilot replied “negative”. He was then asked to try contacting Daly Waters and he acknowledged the request.

Nothing was heard from the aircraft on that frequency and Darwin then tried to call on another. There was no reply and further calls on both frequencies from Darwin, Katherine and Tennant Creek remained unanswered.

Nothing further was heard from the aircraft and it did not arrive at Daly Waters.

At Darwin, arrangements were immediately put in place for an aerial search, initially using a De Havilland Dove and Beech Baron, which would both be available to fly to Daly Waters at first light, but because severe thunderstorms persisted, they were not able to depart until 9am.

Despite this, most of the determined area of probability – from 30 miles south of Daly Waters to 12 miles north and 55 miles to the east – was searched before the day was over, but without result.

Four aircraft were available for the second day of the search, with a Cessna 310 from the Moorabbin charter company joining in and a Department Fokker Friendship also flying up from Melbourne. The primary search area was covered again and it was extended to the north and south as well – but again without success.

Even more aircraft joined for the third day of searching and at 12.20pm the crew of the Fokker Friendship sighted the wreckage of the missing aircraft lying in timbered country 28 miles north-east of Daly Waters and only eight miles east of the Stuart Highway.

Wreckage was strewn over some distance and there did not appear to be any survivors.

A ground party immediately set off from Daly Waters, being guided to the sight by the Fokker Friendship crew, but it experienced considerable difficulty penetrating the thickly timbered bushland and maintaining satisfactory radio contact with the aircraft overhead. It was not until a second vehicle reached the crash side at 9am the following day – four days after the crash – that it was established there were no survivors.

It was established that the aircraft had made initial impact with a tree 35 feet (10 metres) high. There was evidence that the pilot may have unsuccessfully attempted to lift the port wing over the tree at the last moment.

The impact broke off the trunk and several heavy branches and tore the wing off the aircraft, which then collided with a dead tree 70 feet further along and after another 80 feet struck the ground heavily at high speed. Sliding and tumbling, the wreckage continued along the ground for a further 270 feet striking logs and other trees and disintegrating as it went.

There was no trace of fuel in the aircraft and, although the cockpit was demolished, it was possible to determine that the master switch had been turned off.

* The Department of Civil Aviation Australia report, tabled by the Darwin coroner at the inquest, found that “the probable cause of the accident was that the pilot did not give due regard at a sufficiently early time to the availability of alternative courses of action when faced with the situation of adverse weather and approaching darkness in the vicinity of the intended destination”.

Read more

[ Trip revives crash heartache ]

[ The twists and turns of final hours ]

[ ’Those magnificent men in their flying machine’ ]

[ Four states for mates ]